In order to make our releases smooth what happened? What changes did we make and what did we learn? This is the story about how releases changed over time and became what they are today.

It wasn’t always easy for us to promote our code. It took time and effort to get there and a whole lot of iterating. This is our story about how over the course of a few weeks we were able to go from a system with little confidence to smooth regular updates that are downright boring.

SERIES: Deploys Becoming Boring

If you like this post, I would highly recommend reading the series in order so that you can get the full story.Going Weekly

Our first order of business to adhere to The Agreement was deploying weekly, rain or shine.

Deploying weekly was not smooth at first but soon became much better. We still had a lot of habits from our early deployments which resulted in some bad behaviour. In the first two updates we tried to cram more new functionality into the releases at the last minute. This was a risky proposition given our track record and client confidence but we wanted to get more shipped! This resulted in back to back brown paper bag releases that need to be patched right away. Luckily these issues we caught by our smoke tests and thanks to the existing deployment pipelines were reproduced and fixed immediately.

From these initial hiccups we started to catch our stride. We spent more time fixing defects and stabilizing the system. As we got into a rhythm the releases became less important as we could easily wait for the next one and so the old habits and stress of big releases faded. By the third deployment we had polished the promotion process so that is was a single click for each service. As things became easier we started to rotate the team members doing the updates to share the knowledge more widely and further refine our efforts.

We decided to up the ante by doing Continuous Deployment in our Dev environment. When releases passed sufficient testing they were automatically deployed and the necessary high fives performed! Each commit would kick off this cycle and so new deployments happened all of the time during active development. There was so little overhead to each release that we barely noticed that they were happening except for flashing colours on our dashboard. This pressured us to automate even more of the feedback process so that no human intervention was required.

Manual deployments quickly became a thing of the past. We extended our scripts used in the Dev environment to deploy to any other environment. This simplified the process and made it easy enough for more people perform updates. When problems were found they would be fixed immediately which helped make them more robust and resilient. By continuously exercising these scripts we became very confident they would work as intended. No longer was it a process that could only be done by the original contributors but something anyone on the team could do.

Testing

Next step to satisfy The Agreement was to tighten up our quality assurance and testing practices.

A very simple change that we began immediately was performing more comprehensive smoke testing. We verified that entire system could perform the most critical operations. This was done with our clients to share the new releases with them and collaborate more. This was primarily manual in later environments with some automation per service.

In our Dev environment we bolstered our testing with more scenarios that covered the use cases that our clients cared about the most. This started as manual acceptance testing near the end of each release that was time consuming and onerous. Week by week we automated this process so that it was no longer a final stamp on each release but was triggered by every commit as part of the deployment pipeline to act as release acceptance tests. Once fully automated, we could be very confident in each change that was being made to the system and validate new releases faster than ever.

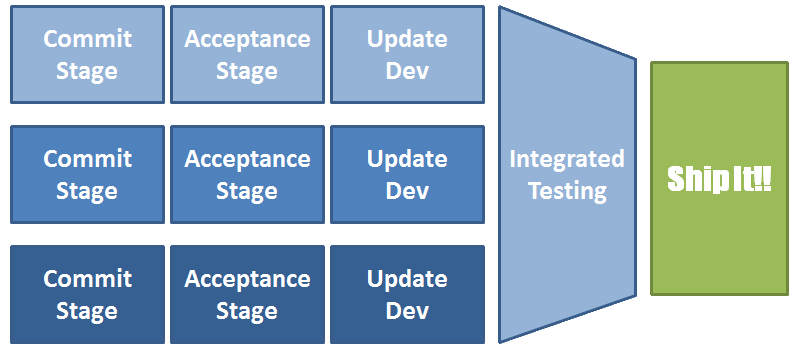

The testing forms two levels, the individual services then fully integrated.

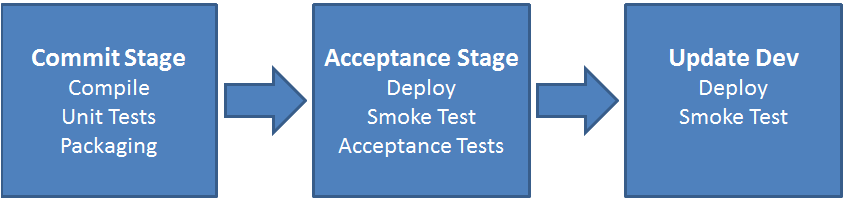

First commit tests run to verify the basic functionality at the lowest level. These are not all unit tests so that we could verify the most important parts of each component as early as possible. Next we typically deploy that service in isolation, execute smoke tests and then run acceptance tests. These tests are more complicated and cover larger portions of the system. They still try to isolate each service but can include other stable collaborators as needed.

We then update the changed service(s) followed by running the release acceptance tests to comprehensively verify the new changes. Where possible we try to keep the other services unchanged so failures can be attributed to the changes. This has been instrumental at finding subtle system level integration issues. Occasionally, we would perform some manual testing for areas particularly hard to check automatically or would provide limited use. We try very hard to automate all of our testing and reduce what needs to be verified manually.

Commits trigger the individual deployment pipelines which are responsible for the commit and acceptance tests. Once each pipeline is complete they trigger the release acceptance tests. This exercises all changes early and often so that we receive feedback right away.

We also started running the release acceptance tests periodically to test the environment. By exercising the entire system regularly at a working state we isolated environmental issues before they caused other problems. Finding infrastructure issues right away helped with finding the root cause and learning what changes were harmful.

Another quality improvement was mandatory code reviews. To maximize learning we would include an expert on the code being modified and someone less familiar with it. Passively knowledge flowed from expert to the unfamiliar raising the team’s ability to contribute across the entire codebase. These reviews were not intended to act as a replacement for other testing but instead a sober second thought and often a fresh pair of eyes to help review automated test cases.

Managing the Changes

To share our updates more effectively we adjusted how we managed, documented and versioned our releases. This was the final part of the The Agreement.

Simple change management began to take form around our regular updates. At first we stuck to a strict weekly scheduled but relaxed the process after we had several smooth updates. Previously there was lots of ceremony and negotiating to decide when and if we could deploy new versions. To gain initial confidence we worked with our clients to perform first several weekly updates. This routine activity became a great chance to discuss other changes that needed to happen or might conflict with planned updates. The extra coordination had resulted in fewer unplanned environmental changes around the planned deployments helping stabilize the environments for the updates.

Releases started to include additional documentation. Prior to The Agreement there were handoffs involving detailed instructions regarding how each component worked within the larger system. This took effort and time away from improving the system and we did not think these documents were helpful. Most requests were for more detailed documentation but our users did not often read or use the tomes we created.

As the automation around releases and testing grew the handoff instructions for deploying and validating the system became obsolete. With smaller releases and one click deployments we were able to slim down the documentation to highlight just differences between the new update and the previous release. More collaboration with our clients helped us focus the documentation on their concerns and use cases allowing it to be more effective and less verbose.

Our biggest documentation breakthrough came when we moved the release differences into source control along with the rest of the code. While this might seem like a small thing it made a very big difference for our team. Developers could maintain their flow while adding features and update documentation all in the same pull request. We use a simple markdown file within the repository for tracking larger changes in each version. These documents are now the developer’s responsibility to keep up to date. No longer can documentation be an afterthought and instead is best done alongside all the other work.

To clearly show a release’s impact we started to adopt semantic versioning. This change in particular felt hit or miss. It started as extra work near the end of a release to bump all version numbers. As a result it would often be forgotten and need to be done on the release day. This was simplified when we started defining the version number with the code instead of in Jenkins or with other artifacts. Like the documentation, developers could proactively update the version number as they made their changes.

Due to our release frequency, it felt like we incremented our version numbers all the time. We were actively developing many of our projects which rapidly increased the version numbers. We tried to reduce the impact of locking down the public API by keeping some project prior to 1.0.0 for longer but this feels like an anti-pattern. Other projects that went to 1.0.0 before the API stabilized have suffered from quickly incremented major versions due to small breaking changes (like 5.0.0+ for one project). Overall, I think that our versioning scheme has been useful but remains an area for future discussions.

Another versioning challenge was around several small projects that had deep dependency chains. Updating these projects would occasionally cause cascading modifications and were impactful throughout the codebase. This immediate code smell showed that our projects were coupled in a bad way. We then iterated on the design to break up these dependencies by flattening them and making some more abstract. This has made the system more modular and flexible which has simplified our testing by allowing stubs/fakes across natural boundaries.

The Effects of Speed

While not strictly caused by The Agreement strange things started happening with our more frequent deployments.

Each new issue that came up was dealt with immediately and then more permanent fixes were put into place to prevent them from occurring again. This included more monitoring and diagnostics which enabled us to find and deal with issues before they hindered the services we had created. We invested further into hardening our environments and isolating the different resources used by each one. This prevented the cross contamination we were seeing and vastly improved the environment stability. Thanks to weekly releases our clients would get the changes right away instead of having to wait weeks for fixes to be deployed.

Another interesting side effect occurred as we continued this process. Early on the updates were quite large but eventually shrunk much smaller. The accelerated releases meant that we could no longer do large sweeping changes to the system and instead needed to think about how they could be introduced incrementally. By having smaller releases it was easier to get the quick feedback we wanted while keeping the entire system stable. Smaller incremental changes continued to improve the quality of our releases.

Such frequent releases meant that releases were always on our mind. Every change we introduced needed to consider how it would impact the deployment and our users. Backwards compatibility became a very important design consideration and needed extra testing/development effort. Although more work was required to keep the code stable we were able to ship new functionality sooner and with less ceremony. Earlier delivery meant better feedback on new features which helped guide future changes. Breaking changes took more time and often spanned multiple releases so there was always a smooth transition. This trade-off was routinely frustrating but we persisted because it helped us make a better product and allowed our users adopt new releases sooner.

Conclusions

We are now able to consistently add new functionality and improve the capabilities of the system safely. We started building things smaller, with better backwards compatibility and with more thorough testing resulting in smoother updates and improved quality. By stabilizing our releases we were able to radically improve. For us and our clients the difference is dramatic.

This isn’t the end; we are still working at improving. In the next part of this series I will recap the shifts we have seen and share where we want to go next.

I would like to thank Michael Swart, Matt Campbell and Bogdan Matu for helping review this and several other early posts.